How to Debug

Ask a programmer how they debug, and they will reveal to you their soul. I'd like to say I'm being a little melodramatic here, but honestly, I'm not. Not only do I think this is a great interview question, but how you answer it strikes to the heart of a deeper question: how do you actually believe people and technology fit together? Here's my answer.

This entire post is going to try and sell you on a process that will make you better at tackling software bugs, but I'd be lying if I said it was mine. This isn't my process, I think it's a deeper method that exists independently of everyone and I happened to discover it through the experience of attacking hundreds of software bugs. This is because I see it everywhere else. For example, it popped up here in Gabe Newell's recent AMA (ask me anything):

Question: Hello Mr. Newell!

I am a college student who intends to work in the game industry after graduation. Do you have any tips for people like myself who want to design games, both independently and with established teams in the industry?

His Answer: The most important thing you can do is to get into an iteration cycle where you can measure the impact of your work, have a hypothesis about how making changes will affect those variables, and ship changes regularly. It doesn't even matter that much what the content is - it's the iteration of hypothesis, changes, and measurement that will make you better at a faster rate than anything else we have seen.

So even if you don't trust me, I hope you can trust the billionaire who runs his company on the basis of this underlying process. But before I break it down for you, there are some factors specific to our situation.

Two Little Big Details #

When you first decide to tackle a given bug, a lot of things happen unconsciously. The most important of these is that every single programmer will build a story about what's happening, and then act off of that. Because humans think in stories. This is important, because --

Detail 1: Bugs Are Generally Unintuitive #

Generally, bugs are unintuitive by nature or they wouldn't have been introduced during development. So I'm guessing our first intuitions probably aren't the most effective place to start down the debugging path. This means that in the absence of good information about the bug, following whatever leap of faith story happens first to form in my head probably isn't a good approach because the other programmers could quite possibly be better than me in general, and certainly were at least closer to the problem than me at the time they were working on it. So on some level, the first intuitive stories that form in my head about what could've introduced this bug will be of lower quality than what other programmers have already thought about during development and I assume a bad place to spend my time to fix issues.

That said, I haven't directly measured this, and I think it would be worth measuring. Because someone with a whole lot more experience than me might have the right first intuitive leaps. The key here would be knowing: at what point does going with your gut become a better use of time than using a little more rigorous process?

Detail 2: Computers Are Bad At Talking To People #

I think computers are generally really bad at giving good feedback to humans. We think in stories, and sometimes I've acted off of the wrong story even when the computer was actually telling me exactly what was going wrong in its terse, log-y way. This is our fault, we've built these systems to be inhumane and unforgiving of human frailties. I'm hoping to build useful tools to reverse this for Ruby on Rails development, but for the time being, this is what we've got.

Here's the approach I use that compensates for these two things:

The Five Steps #

1. In plain english, state the problem and the decision you're trying to reach about it. #

A user has reported that some of their images aren't loading. Figure out what change to introduce to get them working.

Aka, get my story straight and clear about exactly what I'm doing so I can back to it if I get lost in the weeds. But notice there are two parts here: the problem, and the decision. This is because maybe there is a problem, but the decision you're trying to arrive at isn't how to solve the problem, but whether or not you even should or can. Maybe the bug actually doesn't affect anyone, ever, and it was just brought to your attention in a weird corner case. As much as I might seem to be harping on "human intuition" in this post, I'm not. It's good in some places, and not others, and this is a case where you should listen to yourself. Because on some level, you have to trust yourself to know what's important or not.

Bonus Side Note:

Important here, for me personally, is stating that such a change/fix does exist, I'm capable of introducing it, and that my role is just to keep learning about/simplifying the system I'm working on until this happens. I've met programmers who are great at articulating a problem, but unconsciously commit to the idea that they're not capable of solving it. They usually don't, or if they do, they spin their wheels a whole bunch before then. So I figure since this is a great way not to introduce fixes, consciously adopting the opposite mindset of theirs is likely way to do so.

2. What do you know? #

I like to think of this as sort of the "is it plugged in" moment. Start with verifying what you're certain of first, because this will help you form the correct story in your mind. Recently there was a bug on an app I help maintain where things were getting displayed that shouldn't have been. Immediately I leapt into trying to figure out what was going wrong with the complicated scraping & importing script, assuming the bug was located there. Ends up, everything was working correctly, we just forgot to apply the right scope in the view.

3. Based on what you currently know, what are the most valuable next things you could go learn? #

Of all the information I could go get, what's the most valuable? Build a list of these, then as you look over all of them, decide. Sometimes, it's obvious. For example, with the "some pictures aren't loading:"

To start, I would look for common characteristics of the pictures that weren't loading compared to those that were. What if it's all pictures of a certain format? That might indicate to look at what browser & device they're using and/or the css on the page. What if it's all images over 2 mb that aren't loading? Generally, go find the closest piece of the system that I'm certain needs to function correctly in general in upstream proximity to my guess, verify that's working, and grow steadily more specific as to what would be valuable for me to learn based on the circumstances of the bug.

4. Make measurements, reduce your uncertainty. #

People often think of "measurement" as holding up a ruler to something and saying "this is 6 inches," but in this context, I really mean a measurement as anything which reduces my uncertainty about what changes I need to make to solve original problem. And the right measurement tool means anything that can give me good feedback about what the computer is doing. Tests are a good way to get automated/fast measurements of your code base sometimes, but maybe I'm looking for something higher level and the measurement I want to make is higher level and is actually sitting in some documentation or a message somewhere. Maybe I just need to learn how a piece of technology works.

Sub-Step: Rinse & Repeat #

I teeter back to "what am I certain of," "what would be valuable to learn," and "how can I make a measurement with the right tool?" For instance, if at the start I can't even detect what images aren't loading or somehow replicate the behavior I want to fix or get information about what occurred, then that will be the first task. Once I'm able to do that, I'll drop back to "what am I certain of" and go though this over and over until:

5. Arrive at a decision, and act. #

When I have enough information to make a good decision about what change to introduce to fix the problem, I do so. If it's not cost-prohibitive in some way, I'd also like to introduce automated feedback about the prevention of this behavior into the codebase somehow (likely 95% of the time a test), or maybe by introducing a directive somehow via actual behavior in code (rewriting something in a way to prevent the defective output from being possible to occur), or where that's not possible putting it up for human deliberation ("in x circumstances, don't do y, because this allows z to happen"). Probably not ever that last one early on because I don't have much experience introducing or getting rid of rigid organizational rules for people who aren't new to a given domain and need the guidance.

My Personal Touches #

I write stuff down #

I tend to write each step down as a phrase or some sort of word-based affordance to the mental thought on its own line of ruled notebook paper and explain out the full version aloud, because something about externalizing my vantage point to it helps me clarify the story of what's happening faster. I suppose this length would also serve as a great proxy for measuring the relative difficulty for me of each bug I'd tackle.

Alternative ways to solve the bug #

Lastly, if I can't figure out why from a technical POV, it very well could be something utterly outside of my control. For example, they use the app a lot and the internet in their home simply isn't working correctly consistently enough that their images won't load and that's the frustrating symptom they reached out about.

In a case like this, even if I still can't reasonably fix images not loading for the user, maybe I can fix the feeling of it. If there was any discretionary sort of budget built into the project at all anywhere, or maybe just because, I think this would be amazing:

I'd ask the user, between blob fish and tea cup hat parakeet, which picture did they like more? Then get a print of it, get that framed (in a frame that's nice, but not too nice) and mail it to them with a note:

Hey Katie,

Sorry your [AppName] images aren't loading. We understand how frustrating it is when your internet pictures don't load. We've carefully selected a picture, made a print, and framed it for you so even if nothing loads on your computer next time, you'll still have at least one great picture from the internet.

Regardless, we'll keep plugging away to make things right!

Thanks,

Your friends at [App]

Because that would make me feel :)

In Conclusion #

When confronted with a problem, fall back onto this process. It's useful many more places than debugging, but it's a phenomenal area to learn get good at using this process.

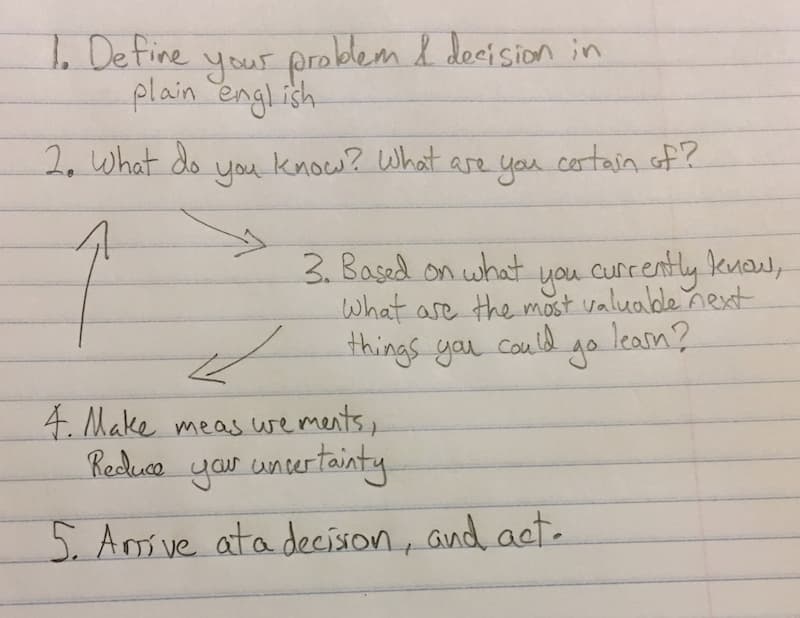

Here's a quick reference (because no blog post would be complete without a terrible, hand-drawn picture):

If you found this blog post fascinating, check out How to Measure Anything to use it to tackle, well, anything.